What’s Wrong With This Picture?

by Richard Vincente

Censorship is a weapon that works best when it’s used sparingly, if at all. It’s the cultural equivalent of a nuclear deterrent.

Most people in marketing, advertising and programming understand this and play by the rules. But the shadowy group of individuals and quasi-legitimate authorities who monitor and enforce community standards have itchy trigger fingers. For them, censorship isn’t just a deterrent, it’s a way of defining what’s acceptable by shooting down anyone who strays outside the fuzzy, fluid lines of public morality.

Today, censorship battles seem like a thing of the past — a relic of the 1970s or 1930s or maybe Victorian England. But they’re not. Skirmishes are still common and, with the emergence of the Internet, the battlefield has changed dramatically.So too have the censors, who keep finding new offenses to shield us from (and, in turn, justify their own existence). Just ask M.I.A., whose middle finger supposedly traumatized billions around the globe on Super Bowl Sunday.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Britain, the quintessential nanny state whose Advertising Standards Authority has issued a plethora of rulings in the past year that can only be described as hysterical. Some examples:

- a Ryanair ad featuring a flight attendant wearing lingerie was banned because it linked “female cabin crew with sexually suggestive behavior”;

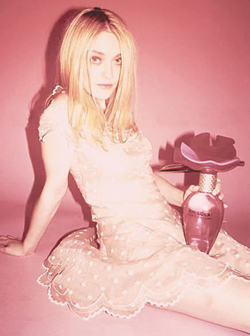

- a Marc Jacobs print ad (above) that featured a fully clothed, 17-year-old Dakota Fanning was banned for being “sexually provocative” because the actress was holding a perfume bottle in her lap;

- last fall, the ASA prohibited billboards within 100 yards of schools from displaying “overtly sexual lingerie such as stockings” — plus a long list of other prohibitions meant to shield children from sexual imagery;

- a Miu Miu print ad in which actress Hailee Steinfeld was shown sitting on railway tracks (fully dressed) was banned because it depicted “irresponsible behavior”;

- an Yves Saint Laurent TV spot was banned because its dancing model may have been implying drug use when she ran her finger along her forearm;

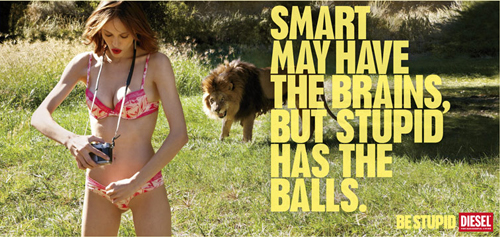

- two print ads from Diesel‘s widely seen “Be Stupid” campaign were banned because, well, they encouraged people to be stupid;

- and the entire spring catalogue for college kids’ fashion label Jack Wills was banned because it contained imagery showing young people partying and getting frisky.

But Britain’s avid censors don’t stop at protecting kids; they’re also looking out for wrinkly moms too. In the past year, the ASA has banned cosmetics ads featuring Rachel Weisz, Julia Roberts and Christy Turlington all for the same reason —photoshopping had given the models unrealistically pretty skin, making the ads deceptive.

And if you think this is a peculiarly British phenomenon, you’re wrong. A couple of months ago, the U.S. Better Business Bureaus’ National Advertising Division banned a CoverGirl ad (below) featuring Taylor Swift for the same reason — no one’s eyelashes could possibly look that good.

These examples point to a disturbing trend: censorship bodies flailing around in search of meaning and purpose in a world where it’s impossible to keep up with the bombardment of media images and the technology used to crate them. The result is that these bodies — which are usually non-government, industry-appointed watchdogs — pass judgments fitfully and erratically, leaving a trail of confusion and mixed messages in their wake.

Politicians in most western countries are loath to get involved, and with good reason; censorship involves too much subjective interpretation of public values, which are always shifting. In the U.S., for instance, the Federal Trade Commission oversees ad standards to some extent, but it mostly limits its purview to those ads associated with weight loss products, public health issues and advertising (especially food products) aimed at children.

The FTC’s division of ad practices is also more interested in truthfulness in advertising than in trying to keep the public from getting aroused (that’s the FCC’s job). It doesn’t pay much attention to what Victoria’s Secret is showing.

Britain’s ad authority, on the other hand, has been emboldened by growing public concern about the sexualization of children. A widely applauded 2011 report on the issue called for new policies to shield children from online porn and laws to protect kids from being exploited in advertising. And it’s had a powerful impact: Prime Minister David Cameron got behind the report and launched a national ParentPort website where the public can report media abuses, and the nation’s leading Internet providers implemented new filtering tools to improve parental control over what their kids see.

‘Protecting children’ is, of course, a social priority that everyone can agree on. But given such a mandate, it can turn censors into zealots and, potentially, open the door to a new wave of suppressed freedoms and repressed public discourse.

The fashion industry and its marketing agencies — who are in the business of creating desirable illusions — have a lot to gain or lose in this matter and need to push back against unreasonable censorship that doesn’t reflect real public concerns.

In particular, the prospect of having unaccountable watchdogs deciding how much Photoshop is too much is frightening. I don’t like a lot of fashion-ad airbrushing, but I don’t want censors speaking for me on this matter.

By the way, that ruling against the Jack Wills catalogue was groundbreaking in part because the banned imagery was the kind of thing used by almost every major clothing brand. But it also showed how easy it is to misuse and manipulate censorship. After all, it only took 19 public complaints (19!) to spike the entire spring campaign of a major fashion brand.

Chilling indeed.

Richard Vincente covers lingerie news daily on Lingerie Talk.

Another great article. It still amazes me that policy bodies, non-governmental or not, focus on the titillation of sexual innuendo as an issue, but remain closemouthed when it comes to pharmaceutical ads as cure alls. Maybe the fashion industry needs a lobby in London and Washington. If nothing else, they will be the best dressed lobby in town.